Live on, Ballard

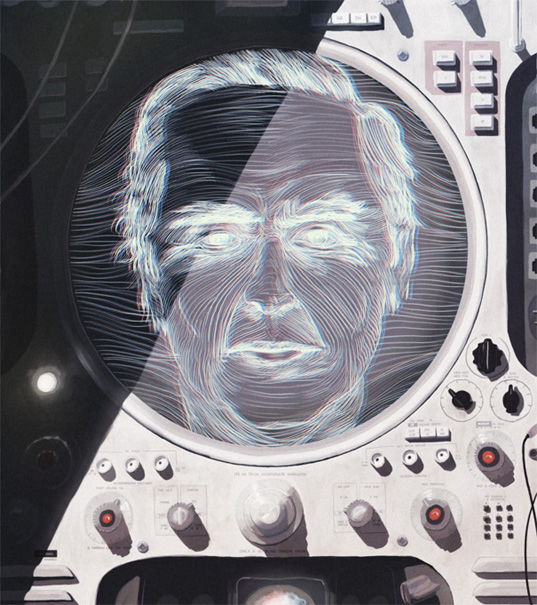

Illustrations by John Lee

J.G. Ballard never said the following:

Today — the beginning of the historical radio era, we are witnessing the mechanization of the human mind. This is the beginning of the creation of a mechanical mentality; the physical side of philosophical.

That was David Burliuk, a futurist painter who enjoyed making collages and talking about himself in the third person, viz. “David Burliuk is the inventor and explorer of the RADIO-STYLE, the one and only style of our epoch.”

But it was Ballard, the author of such masterpieces as Crash and Super-Cannes, who was the inevitable end point of the evolution of radio.

On his death in April, he left us with this haunting sentence in a short story entitled, “THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF J.G.B.”: “B returned home and switched on his transistor radio. The apparatus worked, but all the stations were silent.”

Ballard’s greatest works explored the impact on the human psyche of the mechanized world, how people act when their lives are mediated by technologies layered all around them. He showed us the “mentalization of modern machine society,” something radio had helped create.

Like radio itself, he was frequently ghettoized into the genre of “science fiction”; and like radio itself, Ballard had always been a Utopian. More than reflecting their epoch, the two extrapolated it into the near future.

The kinetic phase destroys the static forms. As in nature thus in life the idea of form is continually destroyed by motion — the very process of life. (Burliuk)

F.T. Marinetti, the futurist poet and pamphleteer, saw very well the sexual and modernistic potential of the radio, its omnipresent intimacy and accessibility. Anticipating the thinking of Ballard, Marinetti immediately understood that the most accurate mechanical expression of the radio age — with its speed, moving parts, power, and sexuality — was the automobile.

I stretched out on my car like a corpse on its bier, but revived at once under the steering wheel, a guillotine blade that threatened my stomach.

“Her hip pressed against the automobile, and the curvature of its door deflected the lines of her thigh, as if the car was a huge orthopaedic device that expressed a voluptuous mix of geometry and desire.

Which one of these passages was written by Ballard, and which by Marinetti? (Ballard’s is the second)

Half a century before Ballard had written Crash, Marinetti fantasized about the “fusion of the machine and the male body; the marriage of the physical aspects of ourselves with the philosophical and technological aspects of our lives”; it was in fact “sexual ambiguity that structured Marinetti’s desire for, and identity with, the machine.” (Poggi, 156, 157).

Indeed, it was Marinetti who gave us the first psychological car crash when, just before proclaiming the Futurist Manifesto, he swerved his car into a watery ditch. As he and his car were wrenched out by some fishermen, he later described not only its symbolic deformation: “It rose slowly leaving in the ditch, like scales, its heavy coachwork of good sense and its upholstery of comfort,” which smelled of the teat of his black wet-nurse, but also of his own symbolic wounds, of his “face covered in good factory mud, covered with metal scratches, useless sweat and celestial grime.” This scene, with its detritus of after-birth and sweat — the uterus-ditch — powerfully anticipates Ballard’s later themes of auto-eroticism.

But Marinetti was as obsessed with Marconi as he was with cars, believing that the radio did for the mind what the automobile did for the body. His vision of radio as an unmediated form of communication that could channel the core aspects of speech from one lived experience to another became the basis for his work on syntax entitled, of all things, “Wireless Writing.”

Yet Ballard, who shared so many of his machine fetishes, was no child of Marinetti — who dreamed of a Danube flowing at 300 kph and for whom the speeding automobile stood for virility and hyper-masculinity — even though so much of the former’s fiction owes itself to the inevitable outcomes of multi-story car parks, phosphorus lights and motorway junctions.

For whereas Marinetti and the futurists viewed the radio age as a mechanisation of the mind, Ballard saw it as the opposite: the mentalization of the modern machine society.

Where the futurists saw in radio the potential for the ultimate liberation that could come from the automation of thought, for Ballard, the car was the new radio. In the post war era, it was the car that represented the modernity that the radio did at the turn of the century: the transmission of voices and their owners from one place to another, modernity, movement and emancipation; speed and its ubiquitous spectre of violence.

But Ballard’s car is a profoundly psychological thing, just as for the futurists the radio-mediated psyche was a mechanical thing.

If Marinetti dreamed of the speed and mechanization inaugurated by radio as a metaphor for (male) libido, Ballard saw beyond this, appreciating the potential of this technology to provide a pathway into a qualitatively different sexuality; in the same way that metal couples with its victims in a car crash, radio waves and their wireless descendants in the internet age achieve a traumatic but liberating congress with the human mind.

... the chests of young women impaled by steering columns, the cheeks of handsome youths pierced by the chromium latches of quarter lights: For him these wounds were the keys to a new sexuality born of perverse technology...the complex wounds that fused together her own sexuality and the hard technology of the automobile. Crash

Such internalisation of high speed communication technology — be it automobile or radio wave — into the human mind creates not only new psychopathologies (as opposed to the more physical pathologies made flesh by futurism’s German and Italian heirs) but also possibilities for hyper-reality.

“Crash is our world”, wrote Jean Baudrillard. “Nothing is really ‘invented’ therein, everything is hyper-functional: traffic and accidents, technology and death, sex and the camera eye. Everything is like a huge simulated and synchronous machine; an acceleration of our own models, of all the models which surround us, all mixed together and hyper-operationalized in the void.”

The radio broadcast was the opening salvo of this hyper-functionality, and by extension, hyper-sexuality. Ballard alone correctly foresaw that the human voice, accelerated by radio waves like a car accelerates a body on the motorway, and heard in a synchronized broadcast across the world even without the knowledge, necessarily, of the original speaker, turned not into a machine, as Burliuk and Marinetti had thought, but rather into simulacrum.

Whereas Marinetti thought we could become more like machines, Ballard realized that amidst a society immersed in and surrounded by the technological, our minds were not getting mechanized: rather, they were copulating with machines. Not for nothing does Baudrillard note Ballard’s view that “sexual pleasure ... operates on the same wave-length as the violence of a technical apparatus.”

For in the end, what are radio waves if not the topographies of orgasm?